Modernization at the mines extended to company houses

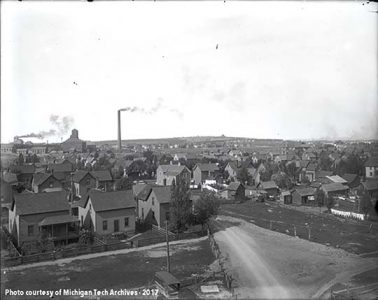

MTU Archives Two rows of worker housing at the Delaware mine on March 15, 1887. The older houses on the left are hewn log houses a story and a half high, while the houses on the right are two-story frame houses with rock foundations. In contrast with the C&H neighborhood in the second photograph, the yards here are muddy and barren. Remains of a fence in lower part of the photograph, and also around the log houses, give the row of houses a run-down tired appearance, and show severe neglect to the neighborhood.

New technologies such as larger, more powerful boilers and steam plants, revolutionized mining and copper production throughout the Lake Superior copper district. But many mine managers saw to it that much new technology extended to employees whose homes were either owned by the company, or were built and owned by employees on company property.

When the mining region was first opened to development by the government in 1843, any investors willing to risk capital to open a mine understood that part of that investment capital would be required to provide housing to its workers. This was simply because, before a company built housing for its workers, there were no other options. The companies were the first to enter the region, and therefore had to provide necessary housing. As time passed and some mines became profitable, housing came to be seen as a means to attract and retain a “better class” of workers. Companies became selective in who they rented houses to, especially after quickly built log huts gave way to frame houses complete with stone foundations.

As Alison K. Hoagland wrote in her book Mine Towns: Building for Workers in Michigan’s Copper Country:

“Housing was needed to attract workers. Good housing, the companies found, along with other perquisites, could also retain workers.”

According to the Summary of Operations of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company for the year ending Apr. 30, 1896, the company constructed three houses for officers (onsite mine management), and an undisclosed number of mine-dwelling houses underwent repairs. Also during that year, a number of houses were connected to the company’s drainage system when the sewage system was completed.

The report for 1898 stated that the company built another 24 houses for workers and an additional four for the officers, and within the next year built another 35. Another 60 were built during the following fiscal year.

A study conducted in 1913 included a survey of mining companies on the subject of houses and employee housing. The survey found that all frame houses owned by C&H were provided with running water, with faucets, while some, but not all, of the houses at the Centennial, Franklin, Isle Royale, Lake, Osceola, Tamarack, and Winona mines were provided with faucets. C&H provided water at no cost, as did Centennial, Copper Range, Franklin, Hancock, Isle Royale, and Lake Companies. But Houghton, Osceola, Tamarack and Winona mines charged 50 cents per month for water supplied to each house.

Hoagland in her book reported that in 1911, 263 of C&H’s houses had indoor toilets, increasing to 325 two years later.

The 1913 study, a report written by the U.S. Dept. of Labor, mentioned that the Mohawk Mining Company’s stamp mill location was the town of Gay, named after company president Joseph E. Gay, consisted of “dwellings for employees, streets, water mains, hydrants, etc.”

As is suggested in the 1908 Quincy Mining Company report, managers did not often place dwelling house maintenance high on the priority list until it became absolutely necessary to do so. Page 12 of the report says that during the year, 37 houses were repaired and painted.

“These houses have long needed such attention,” Charles Lawton wrote in his Superintendent’s Report, “as do other dwellings and buildings about the mine, which will receive like attention the coming season, as fast as conditions about the mine wil warrant.”

The Summary of Operations of the Calumet and Hecla company for 1896 likewise stated that “a considerable number” of the company’s dwelling houses had been repaired during that summer.

Companies viewed what is called corporate paternalism more as investing in their workers. Yes, mining companies benefited in several ways, but workers did, too. They benefited from comparatively less expensive housing on company lands. Rent averaged a dollar per room per month, so that by 1910, a substantially built, but unadorned, house rented for about $5-6 per month, equipped with an indoor toilet, running hot and cold water and firewood or coal sold at just over wholesale prices. Maintenance and repairs and garbage collection were included in the rent, and in the case of C&H, renters were charged a reduced monthly rate for electrical service. Like the other companies, C&H did not generate electricity for domestic use, but contracted with a local electric company instead.

While companies made very few investments in the communities surrounding their properties, they did invest in their workers and their families. Besides housing and amenities, the companies, at least in the cases of the Quincy and C&H, also built and maintained hospitals for their workers and their families, but did not open them to public use. Both companies also maintained bathhouses for their workers and families, which offered showers and baths, but again were not for public use. C&H also built libraries, which were open to the public, as were the schools they built.

While the workers received modern amenities in their houses, rented at very reasonable rates, the companies in return believed they were getting a very stable and content workforce in return — at least it all looked good on paper.

A little deeper look into the paternalism system revealed that in many, many ways, the companies retained a tight control over their employees’ lives and finances. There were strict rules attached to rental and lease agreements. When the Houghton County Traction Company wanted to extend street car service through the Calumet area, C&H Superintendent James “Big Jim” MacNaughton fought it quite earnestly, claiming that street cars would escalate union activity. In the end, he relented, permitting street car tracks to cross C&H lands, but they must be laid in places that would not interfere with the company’s railroad lines. Renters of C&H houses received electrical service at a discount, because that was one of the conditions imposed when the company allowed the electric company to install poles and wires across C&H properties.

Even if the mining companies did not invest significantly in their local communities, they still maintained a tight control or influence over them, as was reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 1913-14. The Houghton County Board of Supervisors was largely composed of mine officers. Most of the other members are engaged in business enterprises, such as the lumber industry, which are closely connected with the mining companies and dependent on them.

“If all the foreigners in the copper range should become naturalized and the working people should vote together,” The Bureau of Labor report stated, “they undoubtedly could control the elections, but fear discharge from employment by the companies, and that means in most cases that they could not obtain other employment in the district, and in some cases that they would lose the homes they have built.”

Indeed, the district had grown since the 1850s. In 1910, the population of Houghton County had reached 88,098; Keweenaw County was 7,156, while Ontonagon County was recorded in the 1910 census, stood at 8,650. With the growth in industry and population, however, also came an increasing gap between the companies and their workers. In the early days of mining, the onsite mine managers, captains and workers all knew each other. By 1910, most of the smaller companies were gone, either closed or absorbed by the larger, wealthier corporations. Companies became impersonal and workers became numbers rather than human beings having names. While companies sought to attract and retain a “better class” of workers, they began regarding them with less and less compassion. The workers sensed it and an air of tension began to slowly rise all across the copper region.

- MTU Archives Two rows of worker housing at the Delaware mine on March 15, 1887. The older houses on the left are hewn log houses a story and a half high, while the houses on the right are two-story frame houses with rock foundations. In contrast with the C&H neighborhood in the second photograph, the yards here are muddy and barren. Remains of a fence in lower part of the photograph, and also around the log houses, give the row of houses a run-down tired appearance, and show severe neglect to the neighborhood.